December 26, 2025

Recent state election victories have strengthened the government’s political capital and enabled bolder economic action

Tax and labour reforms aim to cut compliance burdens, formalise employment and spur consumption and investment

External pressures, including steep US tariffs and global uncertainty, have added urgency to the reform agenda

Despite headline growth above 8%, manufacturing and foreign investment remain below government targets

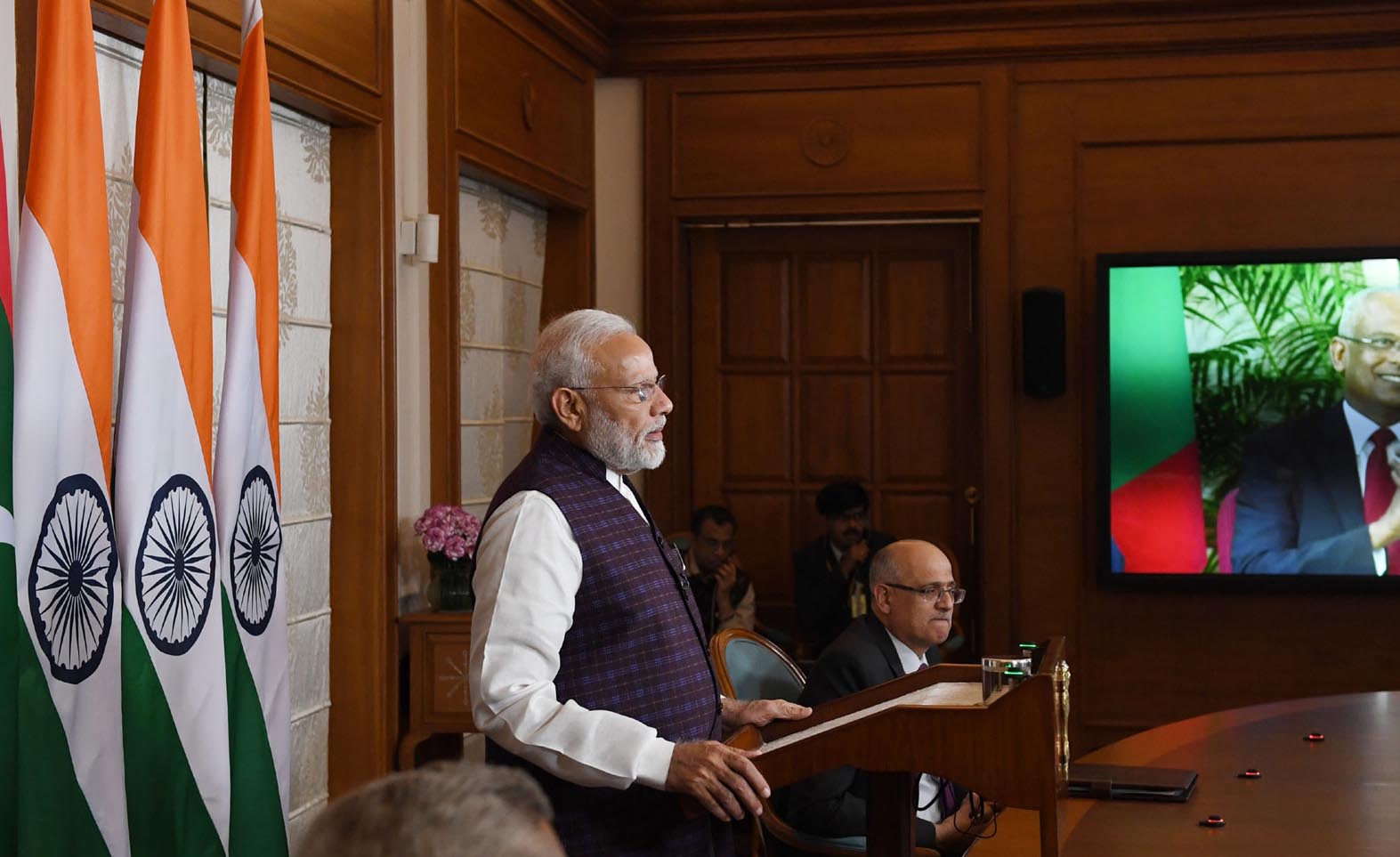

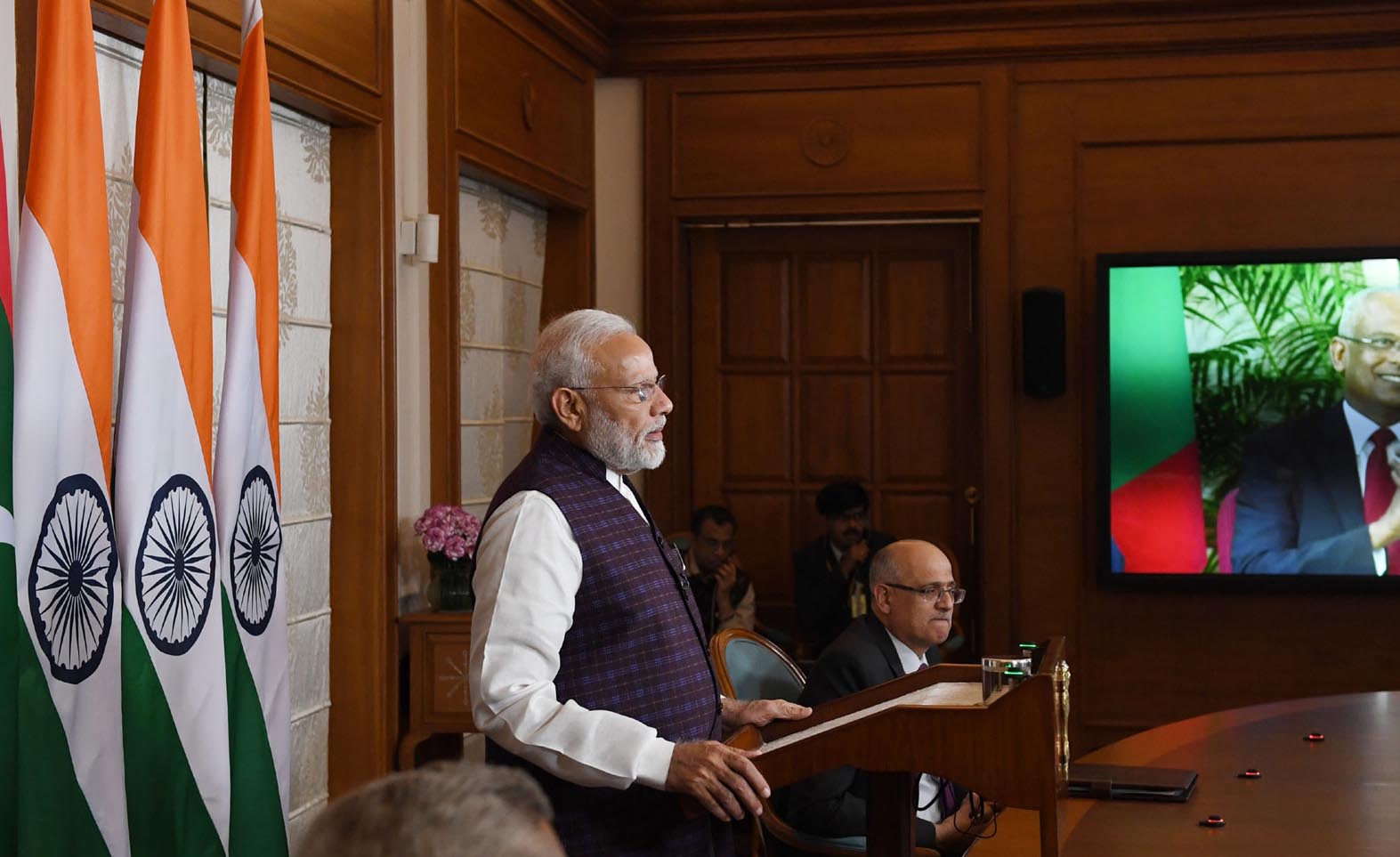

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has signalled a renewed drive for economic reforms after convening lawmakers from his ruling coalition in parliament and urging them to prepare for what he described as a rapid reform push. Weeks later, India has concluded one of its busiest legislative sessions in years, with the government translating recent domestic political successes into a flurry of policy measures to sustain momentum in the fast-growing economy.

Parliament approved proposals to lift caps on foreign direct investment in insurance and open the nuclear power sector to private participation. At the same time, the government had earlier unveiled an overhaul of India’s customs duty regime. These moves were accompanied by a broader effort to ease regulation and signal the intent to reform to global investors.

In recent months, the government has simplified the goods and services tax structure by reducing the number of tax slabs from four to two, enacted long-pending labour codes, and allowed banks to expand into financing mergers and acquisitions. A senior leader from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party said the prime minister typically pushes through major reform packages in concentrated bursts when political and economic conditions align, and argued that the current moment fits that pattern.

Modi has been buoyed by a series of state election victories that have strengthened his political capital. These wins have given the government greater leeway to pursue reforms, even as India navigates a complex external environment.

Although the economy is growing at more than 8% annually, Modi is contending with heightened geopolitical risks, including US tariffs of up to 50% on Indian exports. The government is also seeking to attract multinational manufacturers as an alternative to China, positioning India as a long-term production base.

Political analysts said a combination of electoral gains and global uncertainty had brought previously stalled economic reforms back into focus. They noted that recent victories in states including Maharashtra, Haryana, Delhi and Bihar had given the government breathing space to act decisively.

Economists and investors have long pressed New Delhi to reduce red tape, relax labour laws and simplify tax compliance to stimulate private investment. Policy specialists said recent tax and labour reforms, alongside regulatory easing, could lower costs and complexity for businesses and investors.

The GST overhaul, years in the making, was designed to simplify pricing structures and encourage consumption. Labour code reforms, first announced in 2020 but delayed due to opposition from trade unions and political rivals, aim to formalise India’s vast informal workforce, ease compliance for smaller firms and broaden social security coverage.

Market participants said India now needed a sustained focus on what they described as governance-led stimulus, centred on ease of doing business, an approach they argued the government had begun to pursue more actively in recent months.

Strong growth has also reinforced Modi’s long-term ambition to transform India into a developed economy by 2047, the centenary of independence. Achieving that goal would place him among the country’s most consequential reformers since P.V. Narasimha Rao, who dismantled the Licence Raj and opened India to foreign investment in 1991. Economists estimate this would require an average annual growth rate of approximately 8% over the next two decades.

The challenge has intensified following the US decision to double tariffs on many Indian exports in response to purchases of discounted Russian oil. The Reserve Bank of India has projected growth will slow to 6.6% next year, though analysts said the shift in global conditions may have prompted the government to accelerate reforms.

Political commentators argued that India was facing one of its most difficult external environments in decades, marked by strained relations with both China and the United States, and that the renewed reform push was partly a response to these pressures.

Despite announcements this month by Amazon and Microsoft of combined investments worth $52.5 billion, net foreign direct investment inflows are at three-year lows. Manufacturing remains stuck at about 17% of GDP, well below Modi’s 25% target for 2025, while wage growth has shown little improvement.

Former chief economic adviser Arvind Subramanian said the ultimate test of the reform agenda would be whether it translated into a sustained rise in private investment, which he described as the only durable engine of long-term growth.

Trade talks with Washington have yet to yield a breakthrough, raising concerns for labour-intensive sectors such as textiles. Modi has also resisted opening the agricultural and dairy markets to US imports, wary of the political risks ahead of elections in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Assam, and West Bengal next year.

The renewed emphasis on economic policy follows a second term that was heavily focused on advancing the BJP’s Hindu nationalist agenda. This shift was symbolised by Modi’s inauguration of the Ram Mandir temple in Ayodhya last month, built on the site of a demolished mosque, an event he framed as part of a broader vision for a developed India.

Observers said that, with key ideological goals secured, the prime minister now has greater room to focus on economic reform. At the temple inauguration, Modi suggested India was not far from becoming the world’s third-largest economy, a sentiment echoed by supporters who expressed confidence that he could now focus fully on improving economic outcomes.

Source: Financial Times